Viruses are everywhere.

But, according to Dr. Holly LaFerriere, professor of biology at Bemidji State University, many — perhaps even most — of them remain a mystery to science.

“Not a lot of them have actually been isolated or characterized,” she said.

With antibiotic-resistant bacteria becoming an increasing global health concern, LaFerriere says scientists have refocused their research on bacteriophages — viruses that only infect and destroy bacteria — and phage therapy, which puts biophages to work in medical treatments.

Biophages were discovered early in the 20th century and used to great effect during World War I to thwart dysentery and cholera. Medical research eventually shifted in favor of antibiotics, which were easier to deliver and highly successful in combatting bacterial infections.

“It’s important for us, for understanding viruses in general and for having tools for phage therapy, to isolate and characterize these novel viruses,” LaFerriere said.

Bill Ketola, a BSU senior enrolled in LaFerriere’s Advanced Research Project course, has done just that. During his research work this past academic year, Ketola isolated a previously uncatalogued phage and has demonstrated that it may eventually play a role in treatments for tuberculosis.

For Ketola, a biochemistry major from New Brighton, his road to this discovery started on the football field at Chet Anderson Stadium.

“Originally, I came to BSU because of the football team,” he said. “I had two offers to play Division II college football, and when I got to BSU for a visit, I just loved the campus and the atmosphere of the city. The coaching staff was what I was looking for in a program, and I ended up loving the academic side and the research that I got to do here, as well.”

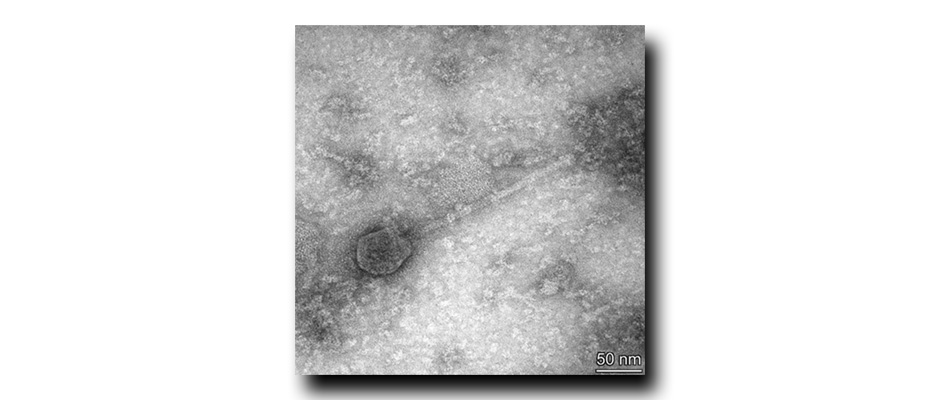

LaFerriere said that Ketola’s work in her lab saw him isolate and characterize a previously undiscovered and unidentified virus.

“Because he isolated a novel virus, he was able to name it,” she said. “It’s a brand-new thing that no one else has worked with. We have the genome, and that supports our idea that this is a new virus.”

Ketola labeled his discovery “Jant.” He coined the name by combining the names of Minnesota Vikings wide receiver Justin Jefferson and Minnesota Timberwolves shooting guard Anthony Edwards, two of Ketola’s favorite professional athletes.

Finding the right sample

Ketola says bacteriophages can be found anywhere bacteria lingers.

“The optimal conditions for bacteria growth are moist soil — you might call it rich if you were a farmer, or if a biologist was planting it,” he said. “If it looks like it would support plant life, it will probably support bacteria growth as well.”

His sample was taken in Richmond, which is about 30 miles southwest of St. Cloud, during a football bye week.

“My fiancé and I went to spend the week at her parents’ house in Richmond, and they live across the street from a corn field,” Ketola said. “When I was looking at the soil in the corn field, it seemed optimal for phage isolation. I took a sample and brought it back here to the lab, and sure enough it ended up having a phage in it.”

In the lab, Ketola added the soil sample to a culture of Mycobacterium smegmatis — a safe, fast-growing bacteria that is commonly used in lab experiments.

“I was very excited, because that was actually the third time that I had taken a soil sample, and the first two times did not turn out well,” he said. “When I finally walked into the lab and looked into my Petri dish and saw the plaques, I was very excited to see that I had been successful and was going to be able to do more research going forward.”

LaFerriere credits some of Ketola’s success to what she calls “lab hands,” or a natural aptitude for scientific experimentation, that she noticed in him right away.

“He’s just able to do the work inside of the lab with ease,” she said. “That is a talent. It’s something that people are born with and they’re very lucky to have. You can build up your skill in lab — that takes time and patience — but he just has a natural talent.”

Ketola said the research he completed this past year confirms that his bacteriophage is a lytic phage, which means it is capable of infecting and killing Mycobacterium smegmatis. That bacteria shares many characteristics with Mycobacterium tuberculosis — the bacteria which causes tuberculosis infections. His research also has confirmed that his phage can kill what are called biofilms created by the Mycobacterium smegmatis

Biofilms are created when individual bacterial cells join together and form a mass, which then secretes proteins, sugars and other material to protect them from the environment. This shell helps biofilms resist treatment from current antibiotics.

“My phage, Jant, is able to kill biofilms,” he said. “Future work is necessary to confirm it, but there’s a good chance that if it can kill Mycobacterium smegmatis, it can kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis.”

‘Amazing to think about

Ketola described the knowledge that his research may play a future role in saving lives as “surreal.”

“This work that I’ve done, because it was required for my degree, that I’ve fallen in love with all of a sudden, it might have real-world implications,” he said. “It’s not just another essay that I had to write or research paper. This is a real thing that might go out into the real world and help people. It’s kind of amazing to think about.”

As a member of the Beaver Football program, it’s no surprise that Ketola credits his success to a team of supporters.

“I’ve had just a great support system around me,” he said. “My parents have been incredibly supportive. They go to every single football game. Even if they have to drive to Minot, North Dakota, or Wayne, Nebraska, they still go to every game. They helped me make my decision to come to Bemidji and then, once I got here, I’ve had a great relationship with my football coaches and with my professors who have been there to guide me and help me through.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do this all by myself,” he said. “I really have everyone else to thank.”

In addition to his support system, he credits the experience he has received at Bemidji State University as key to his success as well.

“I don’t think I could have had a better undergraduate experience anywhere except BSU,” he said. “I met the love of my life here, I won two conference championships here for football, I’ve been to Texas and Colorado for football games. I have had once-in-a-lifetime experiences that I never would have gotten if I wouldn’t have come to Bemidji.”

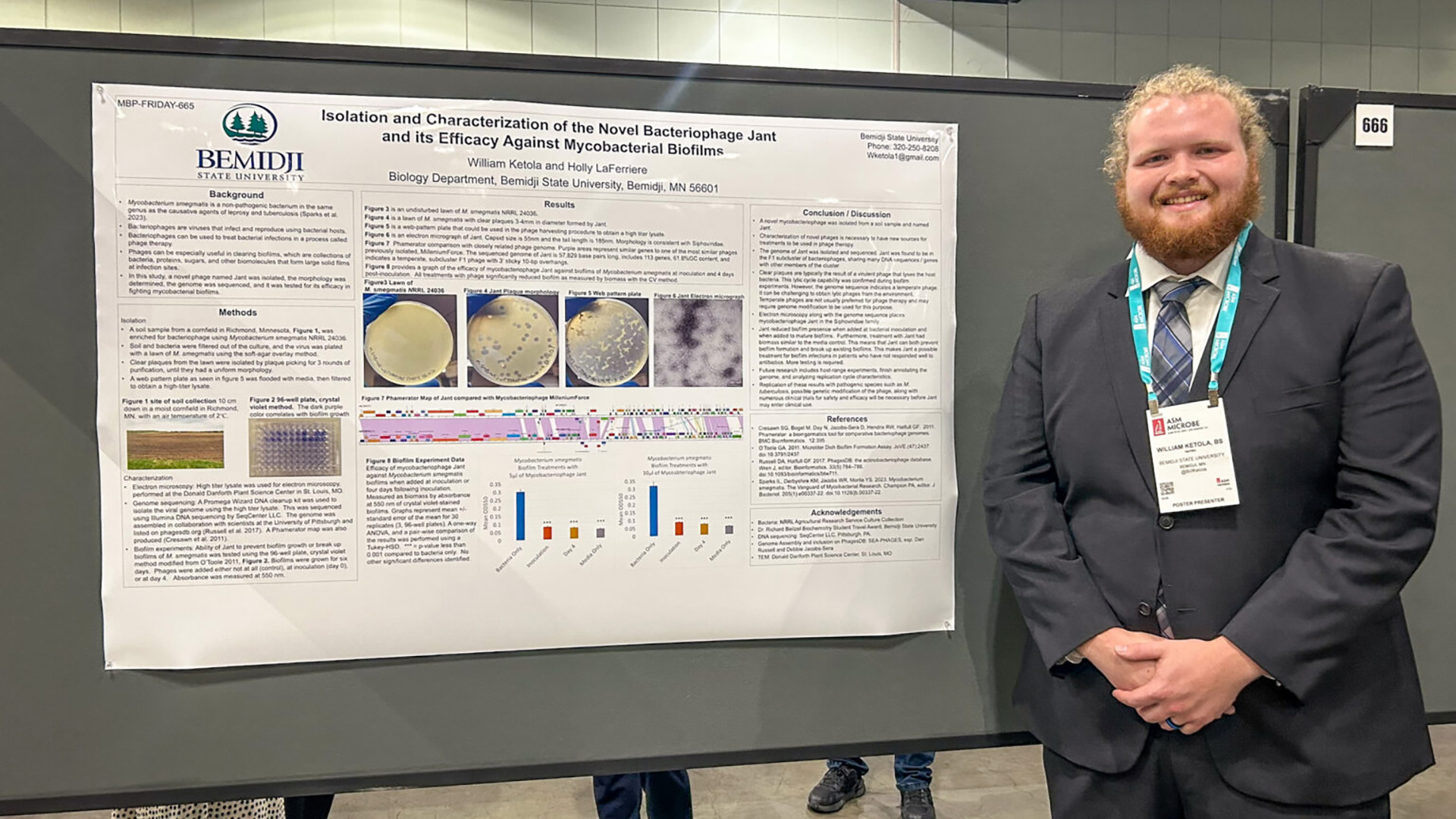

Ketola shared his work at BSU’s Student Achievement Conference in April, and he and presented the discovery this summer at the American Society for Microbiology’s ASM Microbe conference, June 19–23 in Los Angeles. Ketola presented during a June 20 poster session entitled “Friday Fundamental Phage Biology, Phage Defense, and Mobile Genetic Elements.” He was joined by presentations from four other research teams — two from the United States, one from China and one from Japan. The conference was expected to draw more than 5,500 scientists from more than 20 countries.